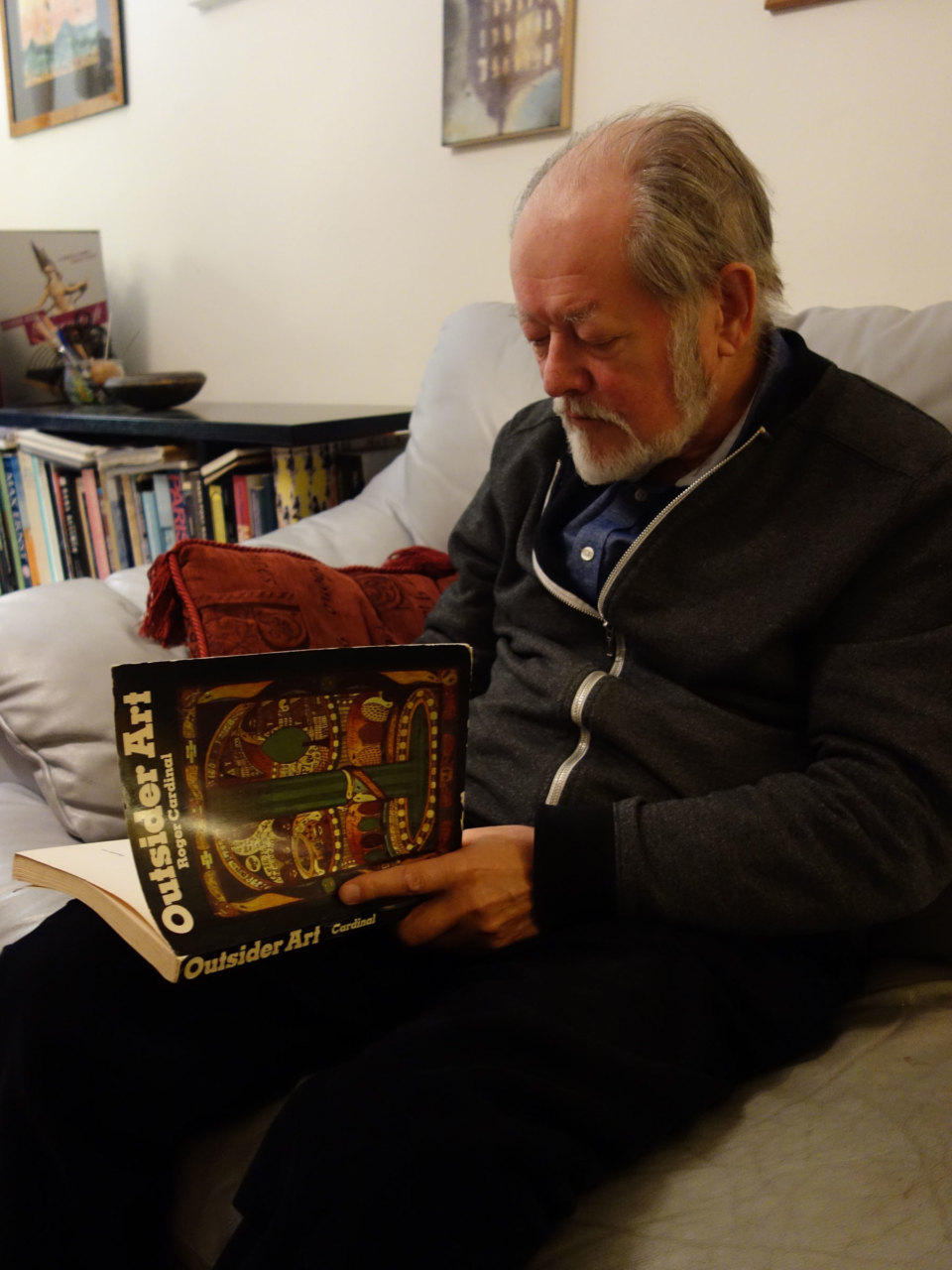

Photo: Nahoko Morimoto

The Path from Surrealism to Art Brut

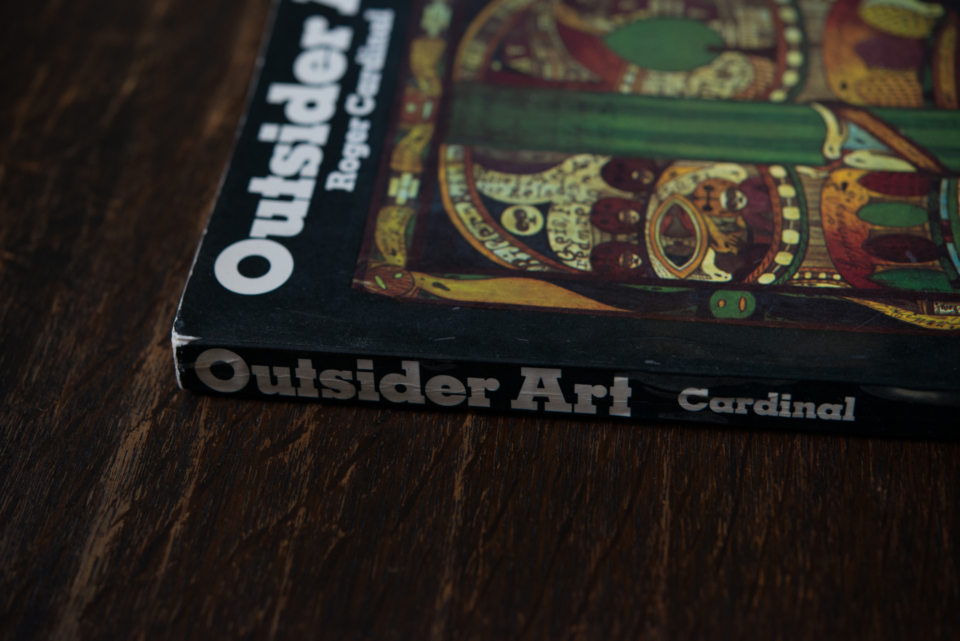

Roger McDonald: You published the historically important book Outsider Art in 1972. What led you to write this book?

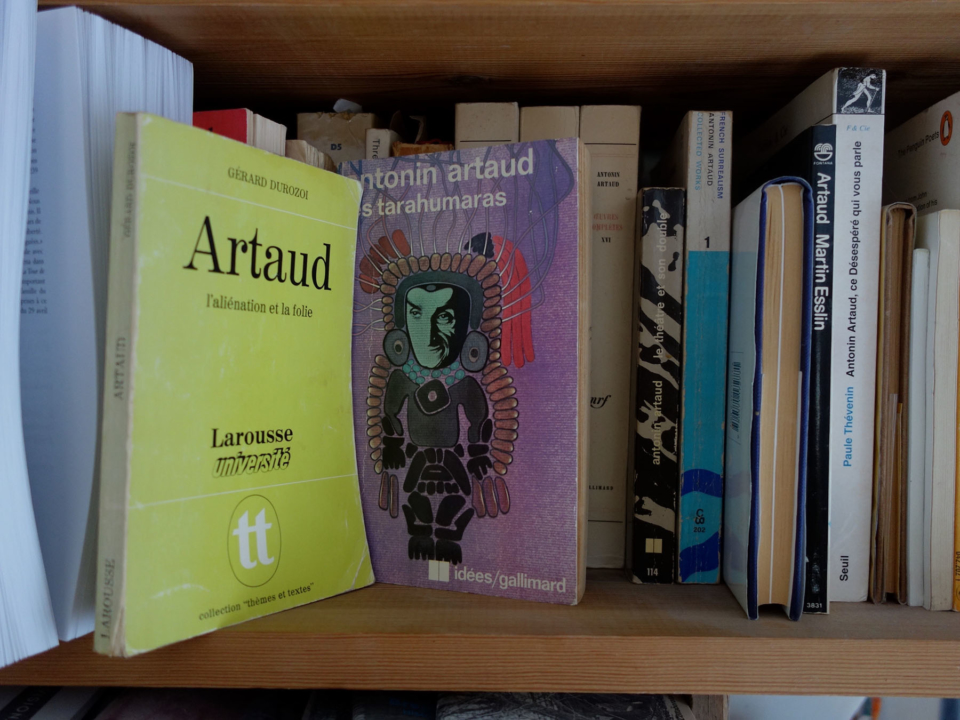

Roger Cardinal: I wrote a book on Surrealism with a friend, Robert Short, titled Surrealism-Permanent Revelation,01 which was published in 1970. Our publisher was a small press called Studio Vista, which was working on the idea of putting out a library of books about Surrealism02 and the avant-garde.03 I had been researching the Surrealism movement in Paris at that time, and I was asked if I had something I would like to write about. I said that I would like to look at the writings and the verbal imaging of Arthur Rimbaud,04 the French poet, wander, and miscreant who fascinated me.

As I was further researching Rimbaud, I realized that writing about Rimbaud was going to be a matter of tracking down material I already had, which did not seem to be original. However, this research opened up my eyes to the fact that there was something else happening in the world of visual art. I suspect part of the reason I switched over to the world of outsider art had to do with the long work we had done tracking down visual material for the book on Surrealism.

At some stage I was asked if I had thought of Jean Dubuffet’s05 idea of art brut.06 While I had little knowledge of what was going on in the world outside academic07 art at that point, I saw that there was a demonstration of some of Rimbaud’s ideas: to take the dream seriously, to let the imagination be a primary element in any creative work, and to rely on things going wrong in a different direction from what you had planned. I think a lot of the thinking around the principles of Surrealism had to do with whether I could make something out of it myself and to know about it. It took me very little time to shift my focus to art brut.

The Revolution Jean Dubuffet was Plotting in the Art World

McDonald: Did you know Jean Dubuffet then?

Cardinal: I had heard about Dubuffet, but had not realized that people who had been influenced by Dubuffet’s philosophy were producing a kind of revolutionary movement. I was carefully observing what he meant and how that fitted into the ideas of the avant-garde.

In his pronouncements he says something like this: “There is something else that you have missed entirely. Take a look at these people who happen to be thwarted in their normal life and development, have had a bad accident happen to them, or those who are heartbroken because their girlfriend never wrote back. There can be so many reasons why people drop into some kind of apathy or depression.”

McDonald: In other words, everyone has the potential to become an art brut artist tomorrow.

Cardinal: Surrealism sensitized me to that because they studied things like suicide. Surrealism made use of anti-right–wing positions, too. For example they took up the Marquis de Sade08 as one of their heroes just to get their enemies mad, which are the bourgeoisie, the educational system, and the political right. These things are bouncing around in the background in the 1930s and 1940s. It became obvious that I had found something really good in Dubuffet’s theories and I began to read his polemic thinking that he was another Surrealist! Dubuffet belongs in the same kind of pantheon of people that one should know about, that one should respect, and that one should travel with in mind. They are part of your intellectual equipment.

McDonald: And it was then that you started writing the book.

Cardinal: I told my publisher about Dubuffet, and they said that this was interesting and that I should find out more about it. At some point I wrote a proposal for a book and The Art of the Artless was the title at one point, I remember.

Cardinal: A lot of outsider art rotates around issues of personality, of asking who I am, which means going deep into the inner self of an individual. So this kind of research could be dangerous, provocative, and damaging to you in such a way that you may never be able to write a book again.

McDonald: The mainstream art world at that time had rigid rules and fetters, which is unimaginable today. Your theme was something that could challenge and anger the art world.

Cardinal: Yes. I was in my early forties and still young enough to feel that I could take charge of this. I went to Paris to get ammunition for this book. It was like a kind of intellectual raid on Dubuffet, who didn’t seem to mind very much. When I went to see him and spoke to him, he had seen my proposal and the first chapter or so of my book. Day by day over about three weeks, I was looking at material, three or four artists per day with guidance from Dubuffet himself, besides going through the pamphlets and a series of books about the general sphere of art brut he authored. Dubuffet was a guerrilla warfare man, really. With these writings, he was challenging the unsuspecting Parisian art world.

McDonald: Against this backdrop, Dubuffet’s art brut encompassed an element that is much more political than today.

Cardinal: Yes, but unfortunately not many people took any notice of his efforts.

McDonald: There is a 27-year gap between 1945, when the term “art brut” was coined, and 1972, when you published Outsider Art. As far as I know, no researcher or critic publicly researched art brut during these years, which makes me think how pioneering you were.

The First Readers of Outsider Art

McDonald: In the book, you speak about an “alternative kind of art” and how Dubuffet was criticizing an academic idea of art. From the perspective of today, where the art world is now so expansive and incorporates almost anything, it sounds like a whole other world. Was it so rigidified and policed back then?

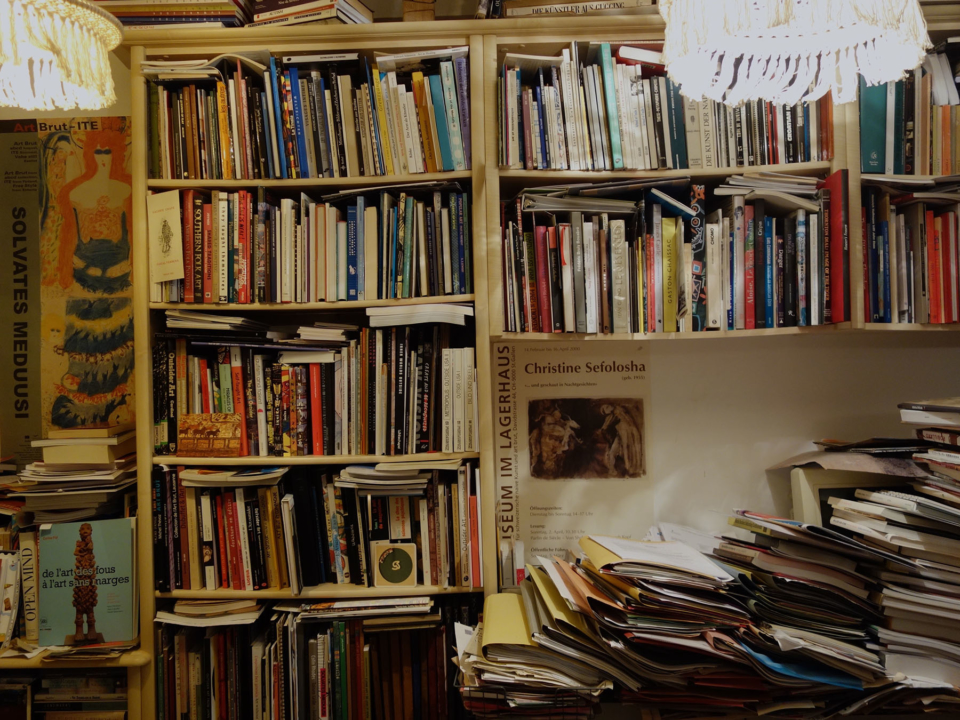

Cardinal: Well, this all happened long ago, and it is long dead. At the time I was starting to write the book and recognize names of artists that I had never heard of. I felt that the time was right for certain things to happen. The fact is, though, that my book was largely ignored. There was a paperback version for the US and a hardcover version in England. It did not sell at all. But many artists found out about it and were ready to be indoctrinated into this alternative world.

McDonald: First it was the artists who took notice of the book, followed by art critics and historians.

Cardinal: In 1979, we had an exhibition, “The Outsiders,” at the Hayward Gallery in London. Dubuffet had already shown some of his collection in public, but outsider art had never been exposed to the wider public up to this point. This was another reason that I was so grateful to him for approving my work. I don’t think he actually read my book, as his English was not that good. But he could see where I was headed and he seemed to be quite pleased about the whole enterprise.

McDonald: Where were you “heading” and what was the book’s actual content?

Cardinal: The book summarizes the important parts of Dubuffet’s work, and I added some other impressive groups of intellectuals that I had found to further enrich the discourse, namely Walter Morgenthaler,09 who looked after Adolf Wolfli and wrote the first book about him, Hans Prinzhorn10, the great collector of psychotic art, and Leo Navratil,11 of the Gugging Collection, who found an artistic quality in mental health patients and cultivated their talents from the 1950s.

Gradually things became normal to me. “Oh, here is another person that had visions,” I would think. “Here is another artist that was said to be suicidal and then began to see things on the wall that they began to copy. And here is another person that had this bad luck in their life and started bringing pebbles from the sea home and stuck them all round their house.”

Read part 2.