Prologue: What emerges from relationships

‘Kizashi and Manazashi’ is an open call exhibition that has been held in Yamagata since 2019. It focuses on the “expressions” (kizashi) of people with disabilities and the “gaze” (manazashi) that follows them. TAKEDA Kazue is one of the people working behind the scenes on the exhibition. She visits welfare facilities and individuals all over Japan to ask about expressive activities that are currently taking place.

What is ‘Kizashi and Manazashi’? Takeda shares an example. At one welfare facility, there was a person who would take equipment outside and line it up in the parking lot on a near-daily basis. Of course, from the perspective of those who wanted to use the equipment, this behavior was nothing but trouble. The staff, however, while perplexed by this person’s behavior, continued to take photographs and document it from their own honest point of view: “Why are they doing this?” They saw in this person’s collection of “mischievous” activities an expression of the person’s will.

“Actions seen as problematic behavior could, when viewed differently, be artistic activity that creates things. This is why the ‘Kizashi and Manazashi’ exhibition introduces the ‘expressions’ (kizashi) that emerge from such relationships,” says Takeda.

![[Photograph]長濱哲哉さんが通う村山特別支援学校本校の廊下を、3人の生徒と1人の先生が一緒に歩いていく後ろ姿](https://staging2022.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/img_nagahama-01.jpg)

Drawing as a form of communication

We set off for Yagashiwa, Yamagata City. Mt. Gassan, blanketed in a thin layer of snow, appeared in the distance as we drove along the national highway. We passed golden rice paddies dancing with dragonflies and orchards growing apples. Crossing the late autumn landscape, we arrived at the main campus of the Murayama School for Special Needs Education. The school building was surrounded by trees and was illuminated by soothing natural daylight. Students’ cheerful voices echoed through the hallways and classrooms.

![[Photograph]長濱哲哉さんが教室の机に向かい、油性ペンで絵を描いている様子。](https://staging2022.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/img_nagahama-02.jpg)

NAGAHAMA Tetsuya (who goes by “Tecchin”) is a senior in high school here. He spends every lunch break drawing in the classroom. “He draws things up so fast—dozens of pictures every day without fail,” says his mother, Naoko. Tetsuya’s sister Shiho, who works as a teacher at a nursery school, was also present on the day of our visit. She showed us some of the works he had created so far. The tote bags and paper bags filled with bundles of drawings that she handed to us were incredibly heavy.

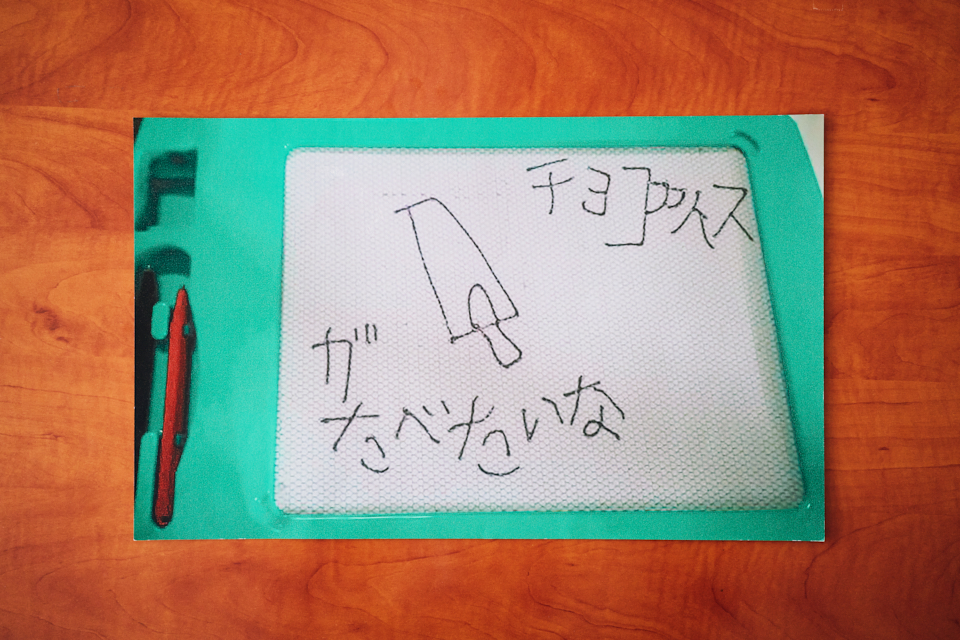

“I think Tecchin’s drawings make use of techniques he developed himself.” I recalled Takeda’s words before the interview: Tetsuya is autistic and is not very good at speaking. As a child, he was unable to express his emotions and often threw tantrums or cried in panic. However, when he reached elementary school, he learned to communicate what was on his mind by showing people pictures and words on a magnetic drawing board, such as “I want to eat chocolate ice cream.” Then, after participating in an open call exhibition when he entered junior high school, he began to express his feelings and desires.

“I was worried that he might not be interested in other people, or that he disliked them, since he had been playing by himself for so long. But after he started drawing, I realized how rich and expansive Tecchin’s world is,” says Naoko. For example, there is a drawing he made of many people and animals smiling and waving their hands. Naoko continues: “Looking at this picture, I could tell that he was happy to see all the daycare members and staff waving goodbye to him as he rode home from the after-school daycare program. He doesn’t show what he’s feeling outwardly, but I guess that’s how he saw it.”

![[Photograph]哲哉さんの姉・志穂さんが手に額装された絵を持っている様子。花柄の赤い振袖を着た志穂さんと、Tシャツ姿の哲哉さんが並んでいる。](https://staging2022.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/img_nagahama-05.jpg)

Drawing has now become Tetsuya’s means of everyday communication. Shiho has long been an observer of Tetsuya’s quest for self-expression and ingenuity in the way he lives his life.

“Through spending time with Tecchin, I became acutely aware of how we can compensate for our weaknesses in order to create a more livable society,” Shiho says. How can we empathize with the minds of other people? This attitude, which she developed naturally while growing up with Tetsuya, is also useful in her own work with children.

![[Photograph]机で絵を描く哲哉さんと、絵を指差しながら哲哉さんに話しかける志穂さん](https://staging2022.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/img_nagahama-06.jpg)

![[Photograph]](https://staging2022.diversity-in-the-arts.jp/admin/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/img_nagahama-main.jpg)